We don't know what 2025 will bring — and that scares us.

This article was originally posted in the Future Minds Lab newsletter. For more of the latest science and ideas on aphantasia, hyperphantasia, intuition and mental imagery, you can subscribe below.

As we enter the first few months of the year, many of us find ourselves pondering what 2025 will bring. Or, if you’re more type-A leaning, that ‘pondering’ probably looks more like ‘ruthlessly engineering’ as you map out meticulous timelines for your goals. And sure, some of what you set out to achieve will likely come to fruition through purposeful effort.

But, one thing we tend to forget when we’re setting SMART goals with rigid deadlines is just how ambiguous and random life can be. The reality is, we know very little about how 2025 will play out — both on a global and individual scale. If you cast your mind back to this time in 2020, the world was blindsided by a pandemic that thwarted our travel plans and kept us locked in our houses for three years.

Of course, the lucky dip of life can bring positive surprises, too. Unplanned-but-not-unwanted pregnancies, financial windfalls and international job opportunities — all 2025 bingo card items that can completely shift your life in a year. But, even the looming (but not guaranteed) possibility of these good things tends to make us feel uncomfortable and unsettled.

Why? Because humans are hardwired to seek out certainty.

The doubt-avoidance tendency

In Morgan Housel’s book Same As Ever (an exploration of timeless lessons that help us navigate risk, opportunity and an uncertain future), he makes a simple-yet-powerful declaration:

“People don’t want accuracy. They want certainty.”

At first, this seems counterintuitive. Surely, in almost all pursuits — whether it’s in medicine, stock investing or town planning — razor-sharp accuracy based on data is always preferable to ‘shoot-in-the-dark’ guesses. However, when you think about how humans really operate (ie. emotionally), the reality becomes clear. In most cases, we would rather have a clear-cut answer (even if it turns out to be wrong than an accurate one — because often, the accurate answer is “we actually don’t know.”

It’s why most of us would rather just have a guarantee that we’re still going to be alive for the next five years, rather than knowing exactly when and how we’re going to die (even though this would likely be more helpful for future planning).

It’s why research shows we would rather get a small, certain financial reward than open ourselves to the possibility of getting a much larger (but not guaranteed) one.

And, it’s why we listen to authoritative people telling us there’s definitely going to be a recession, rather than sifting through patterns and data that might give us a more accurate prediction about financial downturns.

Housel explains that this is likely the result of a common cognitive bias that often leads to poor decision-making: The doubt-avoidance tendency.

In a 1990s talk called ‘The Psychology of Human Misjudgment’ American businessman and investor Charlie Bunjer described this blindspot:

“The brain of man is programmed with a tendency to quickly remove doubt by reaching some decision. It is easy to see how evolution would make animals, over the eons, drift towards such elimination of doubt. After all, the one thing that is surely counterproductive for a prey animal that is threatened by a predator is to take a long time deciding what to do.”

The uncertainty-stress connection

As Bunjer states, we’ve evolved to resist uncertainty, as a survival instinct to remove ourselves from potentially dangerous situations. And, that’s reflected in our nervous system and the circuity of our brains, even today.

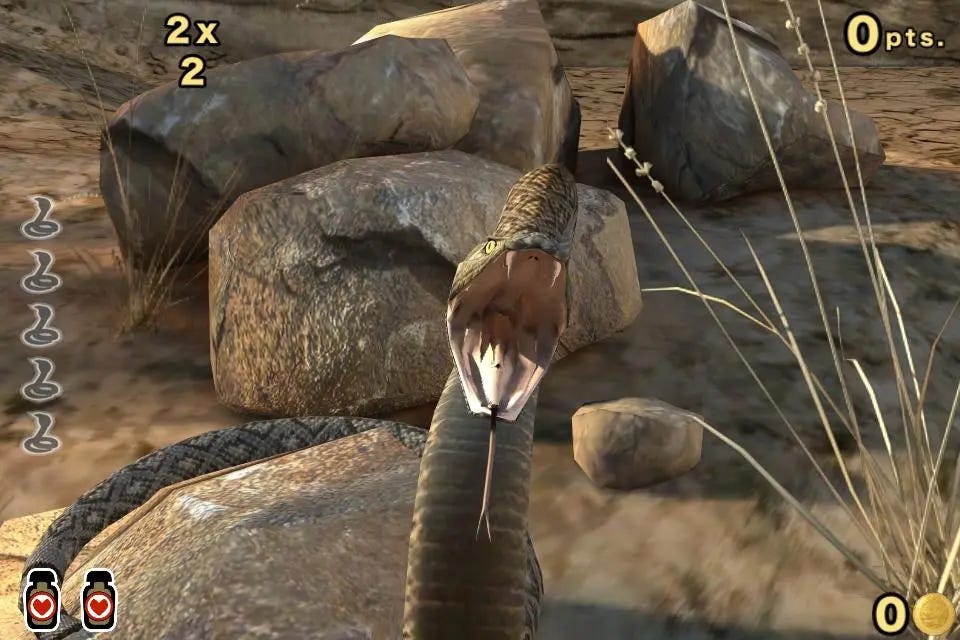

In a 2016 study, researchers had participants play a computer game where they overturned rocks that might have snakes hidden under them — and were delivered an electric shock if a snake appeared. Now, nobody likes an electric shock, so naturally the volunteers attempted to learn the patterns of the games. So, the researchers introduced a measure of ‘irreducible uncertainty’ or risk — which would fluctuate yet remain high.

The scientists measured the participants’ stress through skin conductance, pupil dilation and self-reports. What they found was that stress — both subjective and objective —peaked when there was a 50% chance of the snake appearing. In other words, participants were more stressed when it was highly uncertain if they would get an electric shock vs when it was more likely that they would.

Other studies have linked uncertainty-related stress to high levels of activity in the amygdala (the brain’s threat-response centre) and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (which plays an important role in modulating the stress hormone). This suggests that our fear of uncertainty manifests in the brain and body in a similar way to other forms of anxiety.

However, there’s also another part of the brain that becomes active when faced with uncertainty — the insular cortex, or insula. Tucked behind the lateral sulcus, this hub is divided into two hemispheres: the anterior cortex (involved in reward anticipation and decision making) and the posterior cortex (involved in processing sensory information). This small-yet-crucial region could hold the key to wading through the ambiguity of life.

Intuition as a proxy for probabilistic thinking

When it comes to reaching favourable outcomes in an uncertain world, our best bet is to embrace probabilistic thinking. That is, making decisions based on calculations about how likely something is to happen. The problem is, that we tend to be terrible at this.

Daniel Kahneman once wrote: “Human beings cannot comprehend very big or very small numbers” — and, we’re often dealing in multiple decimal points when it comes to probabilities. Couple this with our deeply-wired desire to make decisions as quickly as possible and it’s not hard to see why we fall short in this area.

But, while we’re not good at probabilistic thinking, there’s a reason our species has come this far. Luckily, we are good at following our intuition, and the insula plays a starring role in this. Whether it’s the hairs on the back of our neck that stand up when someone’s following us in a dark alley or that gut feeling that we should look for another job just before we get made redundant, the insula gives us access to the information stored in our subconscious through interoceptive cues.

When well-honed, our intuition can become something of a proxy for the probabilistic estimations that already exist in our brains. Based on our past experiences, we already have billions of data points around whether that potential job will be a good fit or whether we should move into that new neighbourhood.

By turning down the dial on our emotions, snap judgments and other people’s opinions and leaning more deeply into our intuition, we can navigate the uncertainty of 2025 with less apprehension and more confidence.